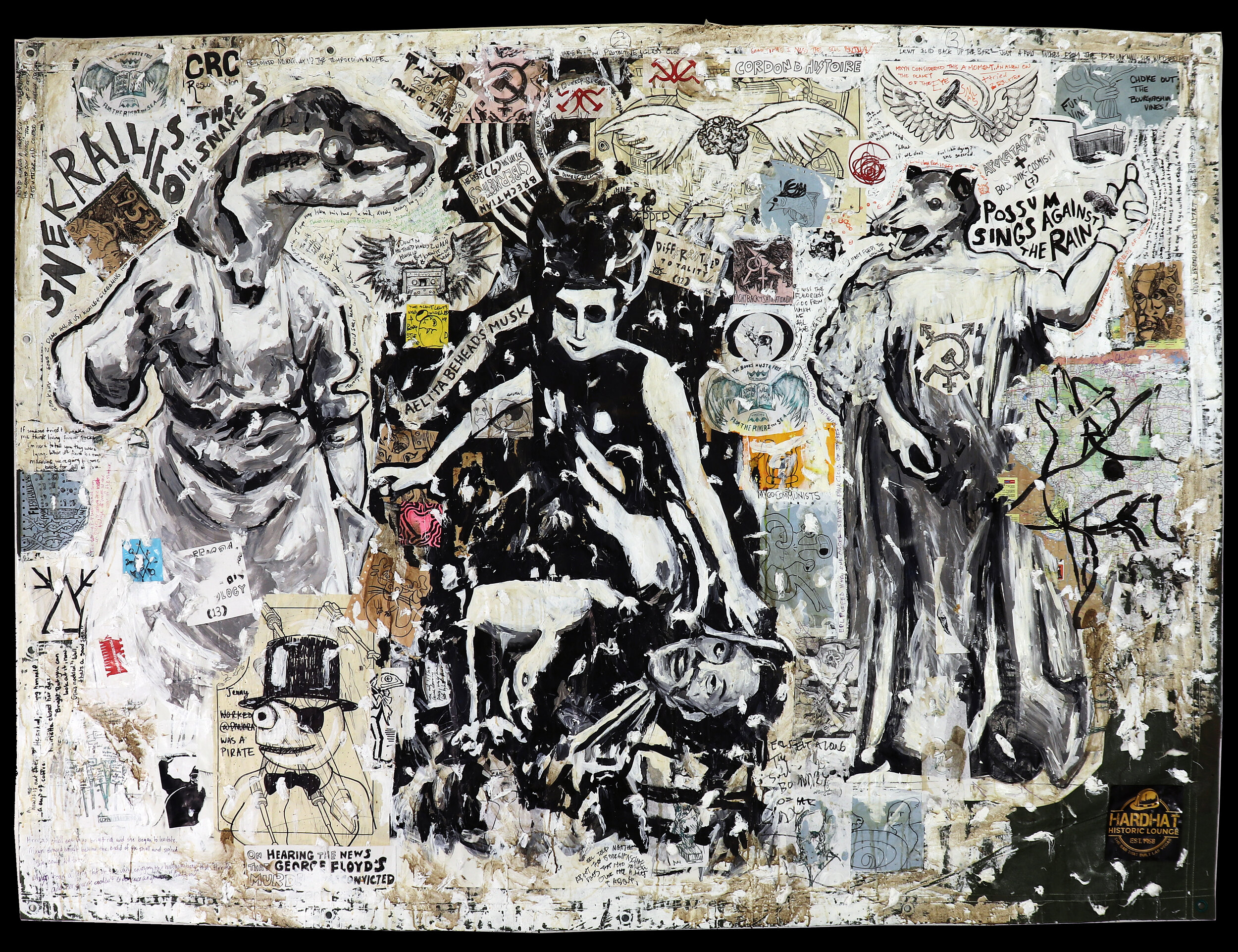

Aelita vs. Elon Musk

The following article was written in the Spring of 2021. Parts of it were cannibalized for the Locust Review #5 editorial, “Working-Class Art Against the Slow Motion Apocalypse.”

“From this point of view [Cosmism], history and the past is a field full of potential: nothing is finished and everyone and everything will come back, not as souls in heaven, but in material form, in this world, with all of their subjectivities, memories, and knowledge. What appears to be a graveyard is in fact a field of amazing potential.” - Anton Vidokle, 2017[1]

Capitalist Realism vs. the Cosmos

IN 2020 billionaire man-child and white progeny of South African Apartheid, Elon Musk, floated the idea of indentured servitude as part of his Mars colonization schemes.[2] This “news” was just the latest iteration of a process by which space and Mars as cultural imaginaries are colonized by an ethos of capitalist realism. Even during the proxy imperial competition known as the “space race,” a sense of collective human achievement in space exploration was considered an ideological necessity. Of course this was rightly challenged. While Neil Armstrong took “a giant leap for humanity” (and US imperialism), Gil Scott-Heron responded that “a rat done bit my sister Nell / with Whitey on the moon,”[3] ridiculing the colossal waste of expenditure while human suffering continued on Earth unabated, particularly for Black persons in the United States. In the post-war Soviet Union, the pretenses toward universalism would have seemed more genuine were they not implemented by a bureaucratic dictatorship that used the language of socialism to conceal the exploitative and imperial nature of the Stalinist state and economic system. Nevertheless, space remained, in terms of broader consciousness, both hegemonic and subaltern, something like a collective-but-diverse imaginary.

The Common Task

WHAT IF the cosmos -- and space exploration -- were part of a great utopian impulse, positioned against war, against privation, and against death itself? What if this imagination was projected onto the surface of Mars instead of Elon Musk’s banal acquisitiveness? This is, in part, the history of Russian Cosmism, an esoteric philosophy that claimed not to be an esoteric philosophy, nurtured by a 19th century Moscow librarian named Nikolai Fedorov. He called it the philosophy of the Common Task. In the 20th century, cosmism would influence the early Soviet avant-garde, science fiction (SF), medicine, and rocket science, mingling with the revolutionary socialist impulses of Bolshevism and the October Revolution, before its eventual marginalization and repression following the Stalinist Thermidor.[4]

Fedorov believed the human race should unite around the common goal of abolishing death and resurrecting all lost generations. He envisioned this would be achieved by a fusion of art and science; wherein art, as the recorded fragments of human performance from past generations, would aid science in this immense task.[5] This aspect of Fedorov’s philosophy is almost (but not quite) a secularization of Christian theology. But, for Fedorov, immortality and resurrection were meant to be literal. Each person would return to life -- or never even depart the mortal coil -- as their unique physical selves.[6] When asked whether or not it would be possible to unite humanity in such a task he would generally remark that the human race was already dedicated to the unifying purposes of war and destruction.[7] To implement the Common Task, space travel was necessary, for two reasons. Firstly, the molecules and energy of the dead, he reasoned, had spread like cosmic dust across the universe. The human race would have to retrieve that material in order to resurrect the ancestors. Secondly, once death was abolished and consigned to the dust-bin of history, the flowering of humanity would be too great for a single world. The human race would need to find new homes among the heavenly spheres.[8] While Fedorov rarely wrote down his ideas, he regularly held court with intellectuals and artists from across Russia, including Leo Tolstoy and Fyodor Dostoyevsky.[9] After his death in 1903, his followers published and spread his ideas across the empire. While they did not gain traction among the broader population they found a fertile reception among a particular layer of scientists, artists, and revolutionaries.

Fedorov’s “Common Task” was an intricate plan as well as a moral philosophy. Every human problem originated with “the problem of death” and all problems were to be judged on whether they contributed to the “disintegration” of life or its “reintegration.”[10] While Fedorov was no socialist, nor even a radical democrat, there is a social dimension to his philosophy, one which complicates the sometimes uncritical union of cosmism with technological utopianism in the early 20th century. “In contrast to some of his followers,” George Young writes, “Fedorov repeatedly emphasizes that technological advance, if pursued independently from advances in morality, the arts, government, and spirituality, and if pursued for its own sake or for purposes other than resurrection of the ancestors, could end only in disaster.”[11]

Nikolai Federov was born in 1829, the “illegitimate” son of Prince Pavel Ivanovich Gagarin. Little is known about his mother. His father went bankrupt financing theatrical productions -- everything from Shakespeare to vaudeville -- across Russia, and supporting his many children, legitimate or not. It was through his father’s aristocratic family that Nikolai was sent to school, and became a provincial teacher. As an instructor he repeatedly got in trouble with school administrators for objecting to corporal punishment. They assumed, wrongly, that Fedorov was a radical democrat of the Jacobinian sort. He wasn’t. It would be more accurate to describe him, as George Young does, as conditioned by a sort of Orthodox Christian asceticism, a mystical ethos that objected to corporal punishment as part of what he would later describe as the forces of disintegration. After taking a job as a librarian at the Chekov Library and the Rumiantsev Museum in Moscow, he rented modest lodgings in boarding houses, slept on a wooden crate, and ate little more than bread and some occasional cheese. When his students would see the state of his living quarters, they would often buy him furniture. Fedorov would promptly sell it and give the money to the poor.[12]

Despite Fedorov’s magnanimous imagination and personal generosity, and his desire for the entirety of the human race to be freed from death, he held Russia’s percolating revolutionary struggle at arm’s length, only coming close to it when a former student was arrested in an anti-Tsarist plot. While protesting that his philosophy was materialist and scientific, Fedorov argued, rather idealistically, the “most serious and destructive division between people was not between rich and poor but between the learned and unlearned.”[13] In addition to this hostility to revolution and socialism, Fedorov believed that the administration of the Common Task should be autocratically overseen by a government not unlike that of Tsarist Russia.[14] Fedorov also incorporated sexist and sexually conservative ideas into his philosophy, for example the concept of “pornocracy,” which held that erotic force lured men from their fathers (their ancestors, and therefore the Common Task), and directed them toward competition and war (for women, of course).[15] Lastly, while there seems to be little evidence that Fedorov was racist -- he literally believed in the resurrection and immortality of all human beings -- some of his posthumous followers were, particularly those more closely associated with practical science.[16]

The decades that followed Fedorov’s death, however, were revolutionary decades, from the 1905 Revolution to the February and October Revolutions of 1917. Cosmist ideas influenced writers, artists, Bolsheviks, and anarchists; many fighting against Tsarist rule, fighting for women’s liberation, and fighting against racism and anti-Semitism. For Fedorov the human race had been “bewitched,” as Young writes, and it needed “to be awakened by a higher magic.”[17] The October Revolution of 1917 seemed to unleash a kind of social magic, an elixir of freed imagination. Old curses could be dispelled and new worlds discovered or made. At least, that is, until the world was “bewitched” again during the Stalinist counter-revolution. Or, in more Marxist terms, until ideology triumphed over consciousness, as the world’s first successful working-class revolution ceased to be working-class or revolutionary in any way, but kept calling itself just that.

Cosmism and Revolutionary Russia

“On the cultural front, the science fiction of Aleksei Tolstoi the paintings of the Suprematists and the Amaravella collective, and Iakov Protazanov’s famous interplanetary movie Aelita all engaged mystical and spiritual ideas of the place of humanity in the cosmos. These embryonic artistic, philosophical, and cultural explorations were important not only because they underlined an interest in the power of modern science but also because they disseminated ideas about space travel that were not simply about technology or modernization.” -- Asif Siddiqi[18]

In the wake of the October Revolution everything was made possible and turned upside-down; “an ostensibly secular brand of millenarianism” Asif Siddiqi writes.[19] Just as Red Guards sacked the Winter Palace as provisional ministers fled, the academicians of Russian art ran away and were replaced by avant-gardes sympathetic to the Bolshevik cause. Among them the Suprematist painter, Kazimir Malevich, who applied cosmist ideals to abstracted and color shapes, meant to invoke the vast cosmos, both as a real and spiritual space, a cosmos that revolution had seemingly put into an imagined reach.[20] Malevich writes:

Earth has been abandoned like a worm-eaten house. And an aspiration towards space is in fact lodged in man and his consciousness, a longing to break away from the globe of the Earth.[21]

Vladimir Tatlin’s Monument to The Third International (1919-1920)

Less consistently influenced by cosmism, but nonetheless conditioned by it, were the Constructivists. Malevich had given the Constructivist movement their name, referring to the relief sculptures that Vladimir Tatlin produced out of construction materials in the 1910s.[22] Tatlin’s famous plans and scale models for an enormous Monument to the Third International are widely known. Less known is that this building, meant to house the Soviet government, would have moved cyclically in real time to mimic the movements of the spheres.[23]

As Asif Siddiqi accounts, public interest in space and space travel mushroomed throughout the 1920s, fed by both “mystical and scientific ideas of the place of humanity in the cosmos.”[24] Konstantin Tsiolkovskii -- the patriarch of Russian rocket science was a cosmist.[25] Public cosmist exhibitions were held across Russia, drawing tens of thousands of people, mixing esoteric philosophy with hard science, including both rocket science and astronomy. Many of these exhibitions were put on by private “cosmist societies” -- without help or hindrance from the state. There were public discussions on interstellar travel among Soviet citizens in the pages of popular magazines that prefigured subjects like the Fermi Paradox. Cosmists lectured to assemblies of factory workers and old-age pensioners, emphasizing to the latter the benefits of reduced gravity on planets such as Mars.[26] An anarchist cosmist movement -- called Biocosmism -- was formed after the October Revolution, supporting the Soviet government while calling for its revolutionary energies to be directed toward immortality, resurrection, and space travel.[27] Biocosmist Alexander Svyatagor echoed Fedorov’s concepts of “personal immortality” and “victory over space,” but connected them to the plans of a revolutionary Russia. Moreover, the Earth itself was to become, for the Biocosmists, a giant spaceship in the cause of the Common Task.[28] Biocosmist propaganda was even given space in the official Bolshevik press. Following Lenin’s death they published a statement in Izvestiia, that responded with a poetics of cosmist resurrection: “[workers] and the oppressed all over the world could never be reconciled with the fact of Lenin’s death.”[29]

The long-time Bolshevik, and sometimes antagonist to Lenin, Alexander Bogdanov, a medical doctor and SF writer, was highly influenced by Russian Cosmism -- in both his medical work and creative writing. As a doctor he was a pioneer in blood transfusions, seeking a means to extend life, doing his part to contribute practically to the Common Task. In 1928, after sharing blood with a patient sick with malaria and tuberculosis he fell ill and died himself. The patient was saved. Bogdanov’s cosmism was fused with his “revolutionary Marxism,” as Richard Sites notes[30] and deeply connected to his ideas of cultural revolution. He linked these varied concepts into a number of his own philosophical ideas, such as tectology -- a sort of precursor or forerunner to systems theory.[31] In 1908 he published the first Bolshevik SF novel, Red Star -- published five more times before 1928[32] -- projecting onto the surface of Mars a communist utopia, without a state or traditional politics, but with, as Sites describes:

[C]lothes made of synthetic material, three-dimensional movies, and a death ray. People are quartered in various kinds of urban and semiurban planned settlements, such as the Great City of Machines or the Children’s Colony. Voluntary labor alternates with leisure and culture, and the drama of life is provided by the never-ending struggle with the natural environment -- not with other people.[33]

The Martian comrades in Bogdanov’s novel debate whether or not to create a socialist colony on Earth. The Martian Sterni “speculates that if Mars established a colony on Earth,” it would be “immediately embattled in an unresolvable war” that would cause communist principle to degenerate into a kind of barbarism, “an island in a hostile sea.”[34] “It is not surprising,” Peter Christensen writes, “that in 1928, the year of Bodganov’s death, a type of sacrificial suicide by blood infusion, the novel was not reprinted. It’s pessimism was too obvious.”[35]

In his 1912 short story, “Immortality Day,” Bogdanov describes a future interplanetary communist society that has achieved immortality.[36]

One thousand years have passed since the day the genius chemist Fride invented a formula for physiological immunity. Injecting the formula into the bloodstream renewed the body’s tissues and sustained its eternal blossoming youth.[37]

The immortal Fride has grown restless. He has visited countless worlds, mastered various artistic practices, explored new scientific avenues, visited his many descendants, gone through several marriages that lasted decades. The world that Bogdanov paints in this story is wonderful. You cannot help but to imagine the possibility of exhausting every road and talent that such a life would provide. But Bogdanov’s Fride wants to know the one thing immortality will not let him know -- death. Eventually he kills himself, taking care to do so in a manner that he cannot be resurrected again.[38] In this way the death of Fride -- the creator of immortality -- prefigures Bogdanov’s own death. Moses doesn’t get to stay in the promised land.

And herein lies the contradiction in Fedorov’s Common Task -- it is an esotericism that claims to be a positivist science, a materialist philosophy that owes much to Christian theology.[39] While this could be seen as a weakness in terms of its pretenses as a positivist scientific philosophy, it is, in terms of culture, part of its strength. Bogdanov’s pivots with and against the Common Task express the liberatory and irrealist character of cosmism. Bogdanov didn’t just want immortality and communism, he wanted everyone to experience equality and immortality as completely free subjects. When Fride has exhausted his subjectivity he is, in Bogdanov’s mind, free to go as he wishes. For Federov there was no question. Everyone must become immortal. For Bogdanov everyone has the right, but not the obligation, to immortality.

If Ellen Pearlmen is correct that cosmism “grew out of a mélange of beliefs,”[40] it is equally true that its spread in revolutionary and early Soviet Russia found cosmism in intercourse with many more. But the flourishing of culture that occurred after the October Revolution was incrementally rolled back. Throughout the 1920s, the revolutionary echoes of 1917 competed with their eventual enclosure. Cosmism “offered itself as an alternative worldview,” Pearlman writes, until the 1930s “when Stalin forbade it, as a number of practitioners had regrettably aligned with Leon Trostky.”[41] But it is no accident that those Bolsheviks who held revolutionary principle closest were also open to the idea that working-class emancipation could lead to the stars and to the abolition of death itself. Cosmism offered both a “fantasy of liberation” and the “liberation of fantasy,” as Siddiqi puts it.[42] When the revolution ceased to be about subaltern and working-class democracy, and instead became a revolution of “development,” the spaces for both fantasy and liberation were eclipsed. In the interim, cosmism was contested between its scientific utopianism and its esoteric “fantasy of liberation,” between October’s expansiveness, and the dreary one-party state to come.

Alexi Tolstoy’s Aelita with and against The Common Task

THE CONTRADICTIONS of the 1920s -- when the Soviet Union vacillated between its revolutionary origins and its future as a conservative one-party dictatorship -- are interwoven with the novel and film, Aelita. The cosmos becomes an alterity of this struggle.

The novel, like Bogdanov’s Red Star, projects revolution onto the surface of Mars. But instead of Mars representing an advanced utopia it is a decaying class society. Written by Alexi Tolstoy, Aelita tells the story of two space explorers from Earth, the engineer Los, and the revolutionary soldier Gusev. When they arrive on the red planet, Los falls in love with the sequestered queen of Mars -- whose father heads up the dictatorial council of engineers, while Gusev foments revolution among the planet’s workers. Aelita, a prisoner of gender and a decadent ruling-class, commits suicide. Gusev and Los return to Earth.[43]

Alexei Tolstoy, a relative of the more famous Leo Tolstoy, wasn’t a Bolshevik, and while influenced by cosmism he wasn’t exactly a cosmist either. He initially supported the counter-revolutionary White Army after the October Revolution. But having relocated to Germany, and with the fascist White Army defeated, he grew homesick. Tolstoy was not fond of Tsarism and was a vaguely liberal humanist, but he was a comfortably wealthy person from an aristocratic background, and was therefore initially hostile to Bolshevism. But, as Victor Serge and others noted, he lived to be a writer, and he felt the loss of a Russian audience deeply in exile.[44] He became one of the “ralliers” -- artists and intellectuals that rallied to the Soviet government in the mid-1920s.

He wrote Aelita still in exile, hoping to prove himself to a Communist government he had previously opposed.[45] As Victor Serge notes, Tolstoy was, on his return, initially an admirer of Trotsky -- as well as all the revolutionary leaders of 1917.[46] When Stalin turned on the peasants in the first “Five Year Plan,” Serge recalls that Tolstoy supported Bukharin and the pro-peasant wing of the Communist Party, only falling in line after Bukharin’s political defeat.[47] He even spoke up against censorship at a meeting of writers in front of Stalin.[48] But as the bureaucratic maneuvers evolved into executions, and as peasants were starved to death, Tolstoy grew more and more quiet, and more and more complicit. Serge writes:

During the height of the famine, [Alexei Tolstoy] one winter night gave a royal party at Dietskoye Selo, with a buffet which set all Leningrad talking, violin orchestra, troikas for driving the guests through the snow. We said: Pir vremya chumy ‘The feast during the plague.’[49]

At the same time, Serge is generous to the person Tolstoy used to be, or could have been, had the world not turned.

[Alexei Tolstoy] was a writer by birth, loving and understanding the human problem, a good psychologist and student of manners, a worshiper of his profession, possessor of a fine feeling for language: everything necessary to make a great writer, if only the despotism and the cowardice which despotism imposes has been absent.[50]

As noted, the period of 1917-1929 was a phase of struggle between the liberatory impulses of 1917 and a slowly unfolding Stalinist counter-revolution. Tolstoy wrote Aelita at the midpoint of this process, right after he repatriated to the USSR, and several years before the executions and show trials. Aelita bears the marks of revolutionary impulse, as well as cosmist influence, but it isn’t exactly a revolutionary novel. In some ways the tragic figure of Aelita -- and her doomed relationship with Los -- seem to mirror Tolstoy’s ambiguous parting with the pre-revolutionary Russian order. It had to go, Tolstoy seems to say, but there is sadness in that fact as well. Tolstoy appears to respect the revolutionary Gusev, but frequently falls into class stereotypes.

Tolstoy’s novel should be situated in the proliferation of SF texts that grew in popularity in the early Soviet Union; a genre referred to as nauchno-fantastika, or “scientific-fantasy,” until Stalinist censorship marginalized and abolished the genre.[51] Aelita differs from both crude pro-Soviet “scientific-fantasy” as well as the critical speculative fictions like Mikhail Bulgakov’s Heart of a Dog (1925) and Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We (1920-1921), precisely in its ambiguity and its quasi-pro-Soviet mysticism, particularly in the bewildering theosophic and anthroposophic stories that Aelita shares with Los in the novel.[52] The stories seem to tell an internationalist version of anthroposophic history on the lost continent of Atlantis. The great city of Atlantis is built, destroyed, and rebuilt, countless times by every race on Earth, making primordial civilization itself international. Whereas anthroposophic mythologies are often deeply racist, even fascist, this seems to be an attempt to undermine that aspect of anthroposophy using its own language. The cyclical cosmology of fascism is de-heroicized and turned into a tragedy of civilization itself, and given the decayed state of Martian class society, a warning.[53] At the same time these passages are not entirely clear. They can be read in multiple ways, for example, reading back into the tumultuous history by which the Rus came to dominate the Eurasian expanse; a history not unrelated to the poetics of cosmism itself.[54] A cosmist reading would lead us to think we must resurrect each of the lost civilizations that once made Atlantis their capitol city. A Bolshevik-cosmist reading would have us do so on the basis of social equality.

Regardless, the novel’s cosmist mysticism, and Tolstoy’s emotional identification with Aelita and Los, led to criticism in the Soviet press. His response was that “Art -- and artistic creation -- appears momentarily like a dream. It has no place for logic, because its goal is not to find a cause for some sort of event, but to give in all its fullness a living piece of the cosmos.”[55]

The public -- as of yet unyoked by Stalinist repression -- tended to agree with Tolstoy. The cosmists were divided. Futurist writers -- some of whom were influenced by cosmism -- disliked the novel and joined in an “anti-Tolstoy campaign” in a coalition of the journal Lef and the Moscow Association of Proletarian Writers (MAPP).[56] The Moscow Society for the Study of Interplanetary Communications, however, initiated the push to turn the novel into a film.[57]

Protazanov’s Aelita with and against The Common Task

PROTAZANOV, LIKE Tolstoy, was also one of the “ralliers,” and one of the few early Soviet filmmakers to have worked extensively before and after October. With little in common with Bolshevik avant-garde filmmakers like Eisenstein, Protazonov’s adaptation of Aelita is, if anything, more conservative than Tolstoy’s novel, although its readings are contested. As Peter Christensen notes there are substantial differences between Tolstoy’s book and Protazanov’s adaptation, elaborating a deep ambivalence even more than Tolstoy.[58] For example, in the book Aelita commits suicide. In the film she leads the counter-revolution on Mars.[59] Christensen ties these narrative revisions to the political dynamics of the 1920s, and argues that the film actually takes sides against Bogdanov and cosmism, asserting a “pro-Lenin” position “that revolution must precede cultural change, rather than flow from it,” attacking engineers (a bourgeois social layer in short supply in the early Soviet Union), and limiting “feminism to the public world of work rather than extending it to the home environment.”[60]

Los and Aelita in the 1924 film

A feminist critique can be applied to both the film and book, as Aelita exists mostly in terms of Los’s gaze in each. Although, in the book she is also a source of knowledge and history, she has little agency, rebelling against her father, as Christensen writes, because she has “fallen in love with the Man from the Sky.”[61] In the film, however, she becomes the agent of counter-revolution. Similarly, in the book, Los is depressed prior to his journey to Mars because his wife has passed from natural causes. In the film he thinks he has shot her in a jealous rage, assuming she was having an affair with a corrupt NEP-man (an agent of the free market under the New Economic Policy of the 1920s). In this way sexist violence becomes a stand-in for other social conflicts rather than something of actual importance in and of itself. Both Los’s wife’s, and Aelita’s, life or death is mostly incidental to Los’s character arc -- an arc that moves him from cosmist dreamer to hard-headed engineer building Soviet Russia. In the end of the film we find out that he did not kill his earthly wife. And the entire Mars sequence is framed as a dream. He did try to kill his wife. But he failed. And then he had a weird dream. The overall message is fairly clear: Stop dreaming and get back to work! That this is communicated, in part, through sexist tropes, only makes it worse.

Contrast this to the love interest in Bogdanov’s Red Star. In this case the visiting Bolshevik, Leonid, falls in love with a Martian comrade who “is neither the exotic princess of Tolstoy’s novel nor the treacherous counterrevolutionary of Protazanov’s film, but rather a worthy representative of a utopian future.”[62]

As Christensen notes, it is not just the framing device and sexism that make the film Aelita more conservative that the book. While Tolstoy’s Gusev is flattened, the working masses in rebellion on Mars are shown as more complex. In the film they are passive receptors of Gusev’s revolutionary wisdom.[63] In the book there are indigenous proletarian Martian leaders. There are none in the film.[64]

Large elements of cosmist influence do remain, primarily in the constructivist costume and set design for the Martian scenes, designed by Isaac Rabinovich, Victor Simov, and Aleksandra Ekster.[65] While these designs provide beautiful glimpses into the revolutionary imagination of constructivism, the fact that they are associated here with a decadent class society undermines their cosmic potential. They become additional flights of fancy to be overcome. The film’s cosmist and constructivist imagery seems to have confounded critics who have therefore missed its (at least partial) anti-cosmist encoding. The movie is, in this way, a document of a fading revolution, a fading revolution projected on the surface of Mars. It is, in part, a rejection of the cosmism that inspired it. At the same time there have been bolshevik-cosmist counter-readings of the film. As Christensen observes, one reading of the film is that Aelita’s counter-revolutionary attempt to install herself at the head of the revolution can be seen as a Bogdanovian parable; that a political revolution without a cultural transformation will produce a new version of class society.[66]

Of course, polysemy being what it is, the social impact of the film was to increase interest in cosmism and space travel.[67] Perhaps this is partly because the source text of Tolstoy’s novel, and the power of the constructivist art within the film, overpower the mostly crude and clumsy narrative changes made in the film. The ambiguities of the film are less nuanced than those of Tolstoy’s novel -- for Tolstoy these were about his actual conflicted loyalties and sensibilities. The film’s ambivalences are so vast -- particularly due to the dream framing device -- that it encourages a certain kind of polysemic reading.[68] This was, after all, a commercial film made with an eye to the Western European audience; a fact that also produced Bolshevik criticism.[69] As Siddiqi notes, Protazanov “sought to produce an ‘impartial’ work, so the negative response surprised him,” particularly from the Bolshevik and state presses.[70] In other words, there is a political economy of meaning at work; an attempt to create a film that would be acceptable to western audiences, the Soviet public, and the Soviet government; a commercial success! Regardless, audiences at the time loved the film. Decades later, the Soviet government even named a Mars exploration project Aelita.[71]

Cosmic Counter-Revolution

AS SIDDIQI notes, the narrowing of the space imaginary under Stalinism was rapid. From dozens of popular articles on spaceflight in the press to none, from open discussion of cosmism to its repression, from a flourishing SF genre to its censorship, from popular cosmist societies to the imprisonment and execution of cosmists.[72] No SF novels at all were published in the USSR from 1931 until after Stalin’s death.[73] In this context, the contradictoriness of Aelita can be seen, in part, as two processes at work in the contestation of the cosmic imaginary. On the one hand, the dreams of a Bolshevik Common Task. On the other, a practical positivism -- and related sexism -- that would someday find banal human expression in the CEO of SpaceX and Tesla. In other words, a confused struggle of cultural signs and codes in a fight against a then-unknown future enclosure of the heavenly commons.

A Proposal for a 21st Century Aelita

THE CONTEMPORARY Bolshevik-cosmist approach to these signs is clear. In our imaginary, Aelita is no longer a princess but one of the many queer heroes of the Martian proletariat. She greets Elon Musk upon his arrival on the red planet. Whether he falls in love with her or not is irrelevant. She executes him as a goodwill gesture to the proletarians of Earth. Yes, someday he will be resurrected. But when that day comes he will just be one of billions. And, as his artificial separation from the masses is the only thing “special” about him, he will weep for a thousand years.

Endnotes

[1] Anton Vidokle, Art without Death: Conversations on Russian Cosmism, (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2017), 11

[2] Tom McKay, “Elon Musk: A New Life Awaits You in the Off-World Colonies--for a Price,” Gizmodo (1/17/20), accessed 4/24/21: https://gizmodo.com/elon-musk-a-new-life-awaits-you-on-the-off-world-colon-1841071257

[3] Gil Scott-Herron, “Whitey on the Moon,” Small Talk at 125th and Lennox (1970)

[4] See Asif A. Siddiqi, “Imagining the Cosmos: Utopians, Mystics, and the Popular Culture of Spaceflight in Revolutionary Russia,” Osiris (23)1 (2008), 260-288

[5] See Boris Groys, “Introduction,” in Groys, ed., Russian Cosmism (Boston: MIT Press, 2018), 6

[6] George Young, The Russian Cosmists The Esoteric Futurism of Nicolai Fedorov and His Followers, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 76-91

[7] Young, 50

[8] Young, 76-91

[9] Ellen Pearlman, 85

[10] Young, 47

[11] Young, 50

[12] Young, 51-75

[13] Young, 59

[14] Young, 88

[15] Young, 89

[16] Siddiqi, 267-268

[17] Young, 91

[18] Siddiqi, 262

[19] Siddiqi, 263

[20] Siddiqi, 280

[21] Siddiqi, 281

[22] For an extended exposition on the Constructivists and their relationship to the Russian Revolution, see Adam Turl, “Constructivism: The Avant-Garde and the Russian Revolution,” Red Wedge (October 5, 2015), available online: http://www.redwedgemagazine.com/online-issue/constructivism-notes-on-art-revolution

[23] Turl

[24] Siddiqi, 261-262

[25] Siddiqi, 262

[26] Siddiqi, 268-74

[27] See Alexander Svyatagor, “Our Affirmations,” “The Doctrine of the Fathers of Anarchism-Biocosmism,” and “Biocosmist Poetics” in Boris Groys, ed, Russian Cosmism (Boston and New York: e-flux and MIT Press, 2018), 59-90, and Siddiqi, 283-284

[28] Svyatagor, 83

[29] Siddiqi, 284

[30] Richard Sites, “Fantasy and Revolution: Alexander Bogdanov and the Origins of Bolshevik Science Fiction,” introduction in Alexander Bogdanov, Red Star: The First Bolshevik Utopia (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984), 1

[31] Sites

[32] Peter G. Christensen, “Women as Princesses or Comrades: Ambivalence in Yakov Protazanov’s ‘Aelita,’ (1924),” New Zealand Slavonic Journal (2000), 107-122, 115

[33] Sites, 7

[34] Christensen, 116 and Alexander Bogdanov, Red Star: The First Bolshevik Utopia (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984) 112

[35] Christensen 116

[36] Alexander Bogdanov, “Immortality Day,” in Boris Groys, ed, Russian Cosmism (Boston and New York: e-flux and MIT Press, 2018), 215-228

[37] Bogdanov, 215

[38] Bogdanov, 215-228

[39] Of course the same can be said, and has been said, of Marxism itself.

[40] Ellen Pearlman, “The Resurgence of Russian Cosmism,” PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art, (41)2, (May, 2019), 85

[41] Pearlman, 85

[42] Siddiqi, 265

[43] Alexei Tolstoy, Aelita (Amsterdam: Freedonia Books, 2001)

[44] Victor Serge, “In a Time of Duplicity,” (February 24. 1945), available online: https://www.marxists.org/archive/serge/1945/02/atolstoy.htm

[45] Christensen, 113

[46] Victor Serge

[47] Serge

[48] Serge

[49] Serge

[50] Serge

[51] Siddiqi, 277

[52] Siddiqi, 277

[53] See in Tolstoy, Aelita, “Aelita’s First Story,” 120-129, “Aelita’s Second Story,” 148-170

[54] See J. English Cook, “Red Films, Blue Prints: Early Soviet Cinema’s Architectural Imaginary,” Framework (61)2 (Fall 2020), 107-144, and Young, 3-11

[55] Siddiqi, 278

[56] Christensen, 113

[57] Siddiqi, 278-279

[58] Christensen, 107

[59] Christensen, 108

[60] Christensen, 108

[61] Christensen,118

[62] Christensen 116

[63] Christensen, 110, 115

[64] Christensen, 115

[65] John E. Bowlt, “The Theatre of the Russian Avant-Garde,” Studies in Theater and Performance (36)3 (2016), 209-218

[66] Christensen, 110-111

[67] Siddiqi, 279

[68] Siddiqi, 279

[69] Christensten, 109

[70] Siddiqi, 280

[71] Siddiqi, 280

[72] Siddiqi, 285-286

[73] Christensen, 112

Adam Turl is an artist, writer, founding member of the Locust Arts & Letters Collective, and co-organizer of the Born Again Labor Museum with Tish Turl. Turl has exhibited their work at the Brett Wesley Gallery and Cube Gallery (Las Vegas), Gallery 210 (St. Louis), Project 1612 (Peoria, Illinois), and Artspace 304 (Carbondale, Illinois). They earned their BFA from Southern Illinois University (SIU) and their MFA from the Sam Fox School of Design and Visual Art at Washington University in St. Louis (2014 and 2016). In 2016 Turl received a residency and fellowship at the Cité internationale des arts in Paris. They were, from 2017 to 2020, an adjunct instructor at the University of Nevada. They are currently working on a doctorate in media studies at SIU, which they wrongly believed was a good way to have health insurance and read books during the collapse of civilization. Adam is also a co-host with Tish Turl of Locust Radio, produced by Drew Franzblau.